Though SOM’s history is more than twice as long as Gordon Bunshaft’s career, the firm and the man are, still, often considered inseparable. Isolating Bunshaft’s contributions to SOM’s 20th-century achievements is no simple matter. The private and temperamental architect died in 1990 and left little in the way of writings or lectures to explain what he was thinking when he helped design celebrated buildings such as Lever House (1952), Manufacturers Trust (1954), Connecticut General (1958), and One Chase Manhattan Plaza (1961).

Nicholas Adams, however, has done about as much as anyone to establish a clearer picture of the man and his influence over a 40-plus-year career. The architectural historian and professor emeritus at Vassar College has been lifting the curtain on SOM’s 20th century story. Since 2002, Adams has published a history of the firm (Skidmore, Owings and Merrill: The Experiment Since 1936), taught courses about the firm and recently published a series of articles about Bunshaft for publications such as Casabella and The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.

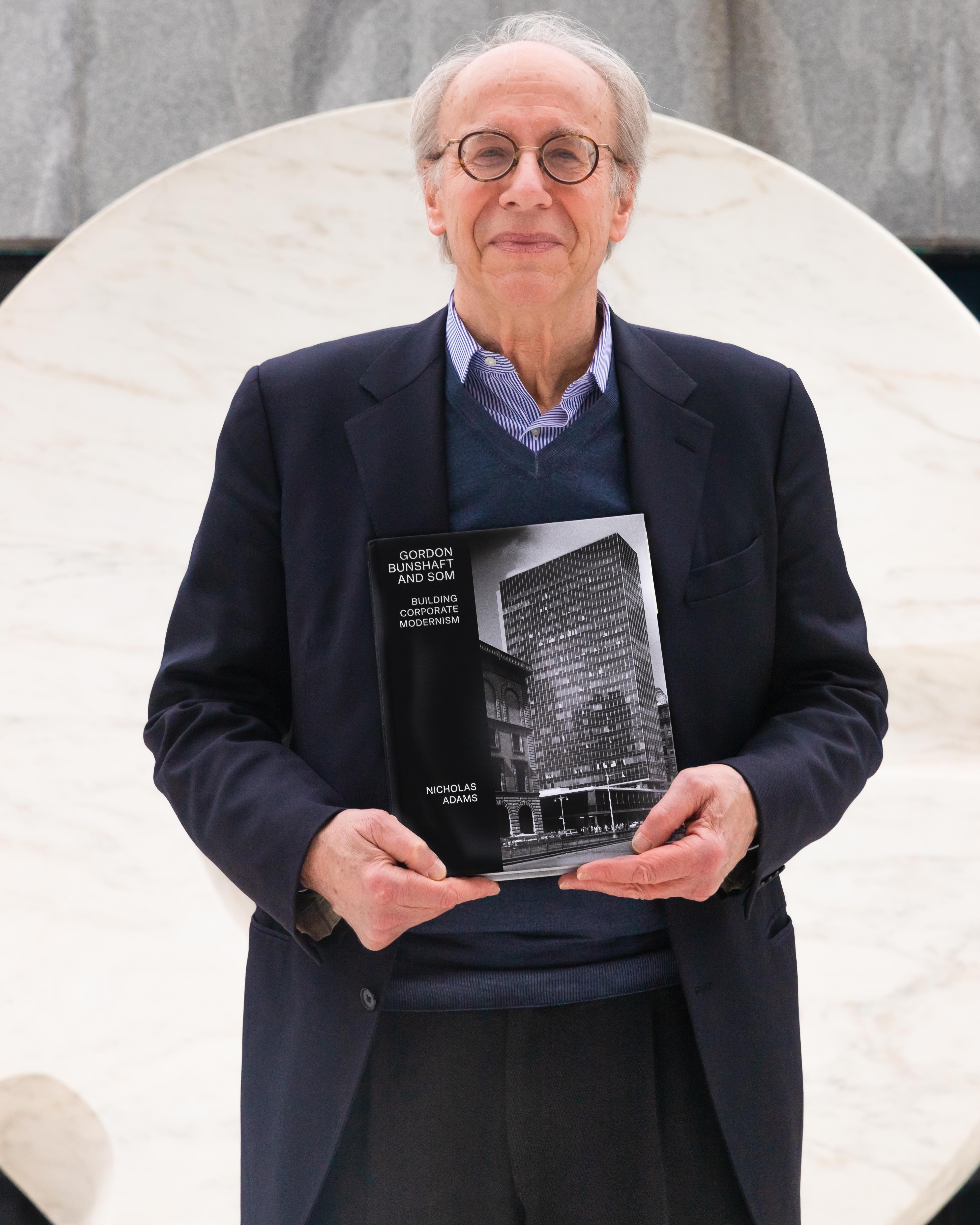

In his new book, Gordon Bunshaft and SOM: Building Corporate Modernism (Yale University Press, 2019), Adams shows how the boy raised by his Jewish-Russian immigrant parents in early 20th century Buffalo made his way to SOM and rose through its ranks designing buildings that exemplified American efficiency and captured the optimism of the postwar moment. Recently, Adams sat down to discuss what he learned about Bunshaft while writing his new book — and why the architect’s legacy matters today.

SOM is famous for the anonymity of its designers. Buildings are attributed to “the firm” or SOM. How did you identify Bunshaft’s buildings?

Nicholas Adams: Bunshaft was very proud of his buildings and their success but he was also keen to shift the limelight to himself. He collaborated on an earlier book with the historian Carol Krinsky [Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (1988)], and identified some 38 special buildings for which he claimed credit. The other partners were not necessarily keen on this personalization but he was brusque, decisive, and most of all, he was incredibly successful. His words and his decisions had weight. For example, Lever Brothers reported that they had received over a million inches of commentary about Lever House from opening day until mid-1959: that was “free” advertising, you might say.

But Bunshaft worked at SOM for over 40 years — was he really only responsible for 40 buildings?

No. He was involved in many more and the book documents many of them. But his involvement took many forms. He might not be the senior design partner — but as another partner commented, “he stuck his fingers in” wherever he could “and in effect had quite a bit to do” with other people’s projects. So the book tries to capture those buildings — Bunshaft’s octopus-like reach within SOM. Furthermore, because of his success and that of the New York office, the other offices in those years (Chicago, San Francisco, Portland) would reach out to him or his team for help. Though he is not known as the designer of Inland Steel (1958) in Chicago or the Air Force Academy (1961) in Colorado Springs, he had plenty to do with them.

You refer to “Bunshaft and his team” or “Bunshaft and SOM” in the book. What does that mean? Was he not responsible alone for the designs?

This issue goes to the difficult questions what Bunshaft did and what others contributed. Architecture is inherently collaborative. We can never think of SOM’s work — or the work of any firm — as belonging exclusively to the architect’s name attached to it. Bunshaft’s buildings are not built by Bunshaft, they’re the work of an entire team, that begins with the client and goes to the person who drives in the last nail. The identification of specific roles for individuals at SOM has always been problematic, partly because people were often shifted in or out of projects. Bunshaft also had little interest in crediting others: basically, he wanted to be seen as an artist.

So what did he actually contribute?

We have to think harder now, rather than just saying casually, “Gordon Bunshaft did Lever House, Beinecke Library, or Union Carbide.” There’s an entire team of people involved, so how did Bunshaft arrive at the particular solution? What did he offer and what did those around him provide? Those are much harder, more interesting questions and my book attempts to answer them. Bunshaft indeed brought a high design sensibility to the process of making buildings. He molded a group of disparate people into teams, he had a remarkable command of materials and technical aspects of putting a building together. He understood how long it would take, and how much it would cost. Their job was to interpret his ideas.

So in effect they were his hands. You say that Bunshaft drew very little—some back of the envelope sketches that the design team then worked up.

That’s right. The senior designers and the teams that worked for him had one goal: to see the ramification of his ideas and present them so that he could pick the best one to develop thoroughly. But he had another advantage. The remarkable thing was that in many instances, he was not only the senior design partner overseeing the design, he was also the senior administrative partner, deciding how much money would be spent on a project. Generally speaking, that’s unheard of at SOM. The administrative partner oversees the money, the designer oversees the design, but he was sufficiently trusted (or sufficiently confident) to do both. There was resentment, for sure, but he had received laurels from clients, the public, the press, and other architects.

Would you say that his skills were administrative — playing the jungle of office politics?

That’s overstating it. He also drove people on with his own design sense, and they agreed to work for him and meet his standards — and in that mixture is his particular greatness. The question of what it is he brings as a mark of his genius needs to be fleshed out a bit more and in that process he also takes ideas from other people. He would even admit that. Paul Weidlinger schooled him in concrete construction and, in at least one instance, he admitted that Nat Owings (the co-founder of SOM) had the idea for turning Lever House at right angles to Park Avenue. I think we have a duty to try to bring into relief all the people who worked with him, and we should make more about people like Natalie de Blois, Roger Radford, Sherwood Smith, Fred Gans, and senior designers on many of his projects.

You make it clear that he was not an easy colleague, an architect who was often rude to colleagues and family.

He was a force. When he got back from the war in 1946, Owings told him, “You’re coming to work with me in Chicago,” and Bunshaft said, “No, I’m going to New York.” Owings tried to fire him then but it was eventually agreed he could go to New York without accrued privileges. He was fired again over Lever House and again over an interview he gave to Newsweek in 1959 in which he claimed to be the only person at SOM who did the designing. Each time he managed to work his way back in.

“He aspired to the status of the painter or the sculptor.”

He was not an easy person to work with. You had to be able to tolerate his straight speaking and the other partners often kept him away from clients. He might storm out of meetings. Smith College’s president referred to him as “your stubborn Mr. Bunshaft.” Jack Heinz once spoke about eventually civilizing him, and people did say he mellowed with age; even so, he did not behave conventionally.

Why did people put up with him?

Success is a powerful inducement. And SOM, in a general sense, had the wind at its back during the 1950s and early 1960s. Those glass and steel curtain wall buildings were a sign of modernity and efficiency. And there was no question that he saw solutions where others stumbled.

You’re not a psychiatrist but do you have any inkling as to why he should have been so difficult. Was it a pose — the architectural heavyweight, the star that wants things his way?

I was puzzled by that too. I talked to a therapist to try to picture how someone could end up like that. He was an only child for the first nine years of his life, and described himself as being spoiled and coddled, by his mother in particular. He was probably dyslexic, so there’s a certain amount of frustration around using words — he tried to train himself to be quiet. To say nothing.

He was an insecure man, and as with many insecure people, his best defense was a good offense. You know, he was not a creative dynamo. In school, he would circulate around the drafting room and take the best of every project around. He wasn’t copying any one of them, but he took the best of all those that were around and put them into his projects. SOM suited him perfectly in that sense because he could set two or three people on different things and then say, “that’s the one we’re going with, we’re not wasting our time on anything else.” His decisiveness was a real asset.

Who did he look up to among his contemporaries?

There were three people he was most drawn to: The artists Henry Moore and Jean Dubuffet, and Paul Weidlinger, who was the only engineer he looked on consistently with admiration and with whom he collaborated.

He had his limitations in what he thought of other architects. He was interested in Gropius. He knew and admired Alvar Aalto. The most important architect in his world was Mies, but he also thought Mies had one idea and did it over and over again. Mies liked to say he wanted his buildings to be good, Bunshaft wanted his buildings to be good and interesting. There’s a playfulness in Bunshaft’s work that isn’t present in Mies. He was not a person who was given to being a follower but he also recognized his limitations. Regarding the Lever House, at one point he says that Le Corbusier would have done a more interesting building. Le Corbusier was certainly a strong influence.

You describe the shift in taste that occurred in the 1960s with the rise of postmodernism. How was Bunshaft viewed then?

Bunshaft was repulsed by the historical ornament of postmodernism. He was a modernist: that was certain. And the postmodernists loathed him. Words like “paradox,” “irony,” and “subjectivity” have no place in Bunshaft’s vocabulary. For Bunshaft, there was no intersection with a critical examination of architecture. When I met Natalie de Blois, one of Bunshaft’s favored senior designers, I’d ask why a certain thing happened with a building and she’d say “it was the logical thing to do.” Then I’d ask, why this form? “Well, it was the obvious form to use.” Natalie was well-aligned with Gordon’s thinking and she had a sharp sense of humor and was not particularly easy to deal with. I never met Bunshaft, but she seemed to reflect his style of thinking.

So in the 1970s Bunshaft designed large-scale concrete buildings like the Hirshhorn, the LBJ Library, 9 West 57th Street, and the National Commercial Bank in Jeddah. And one has to ask why? At the time some critics took an essentialist position: it was masculine arrogance. But I think there’s more to it than that. Clients wanted monumental buildings and Bunshaft knew with his heart of hearts that you could not tell someone “no,” just because it wasn’t fashionable.

He aspired to the status of the painter or the sculptor. And his buildings became more sculptural, more like objects in space. He also served on the Commission of Fine Arts in Washington — and had some experience of monumental architecture there. When it came to a Presidential Library or a National Bank, he wanted his buildings to have that sense of permanence that he had admired in European architecture.

Do you think those projects will ever be admired by a broad audience in the way that Lever House or 140 Broadway are?

It’s too soon to say. [Laughs] As a historian I do the past, not the future. 9 West 57th Street was attacked for being hostile to the urban environment. Today, next to some of the needle towers going up nearby, it looks as gentle as can be and it is still an exciting building, a surprise as you come down 57th Street. To me, it seems to be one of Bunshaft’s answers to the stiff-frame of Mies’s Seagram Building.

We are seeing a lot of his buildings under threat or destroyed today. Union Carbide is being taken down; the renovation to the Albright-Knox; the changes to Lincoln Center. Emhart [Corporation in Bloomfield, Connecticut] has already been taken down as has the Southern Life Insurance Building in Houston.

No question. These are buildings under threat. Connecticut General has long had a death sentence and the renovation to Manufacturers, though it left the frame in place, largely gutted the interior. Many things are going on here. More profit from taller buildings; bling brought to empty spaces, functions change. That said, it is a loss. At Buffalo’s Albright-Knox Art Gallery (1962) that extraordinary contrast between old (Albright) and new (Knox) will no longer be visible: it was a brilliant thesis and antithesis without a synthesis, old and new had their place. At Lincoln Center (1965) the once peaceful open plaza allowing generous space around the great Henry Moore sculpture has now been chopped up. Perhaps the greatest loss has been Bunshaft’s own house (1963) on Long Island, which he and his wife Nina used as a weekend retreat. They never had children and so their home was not designed for a family so much as it was for art. It had his Miròs, Picassos, Moores, and Dubuffets and was surrounded by a remarkable landscape created by SOM’s Joanna Diman. Bunshaft donated the art works and the house to the Museum of Modern Art without restrictions. Though MoMA has kept some of the works, many have been sold. The house was also sold and eventually demolished. These are decisions we may come to regret, if we don’t already.

Where should people go to see the best of Bunshaft?

If you can’t get to Jeddah for the National Commercial Bank (1983), Lever House at Park Avenue and 52nd Street, brilliantly restored by SOM, and 9 West 57th Street (1974), both in New York are special. No one should miss 140 Broadway (1967) with its brilliant Noguchi sculpture or the Beinecke Library at Yale University (1963). The American Republic Insurance Building (1965) in Des Moines, and the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum (1971) in Austin, are also spectacular. The American Republic headquarters has recently been expertly and lovingly restored by Rod Kruse of BNIM. These are buildings to visit and care for well into the future.

Read more about Gordon Bunshaft and his work: